“Rainy afternoons are perfect for one thing: sipping mezcal.” – Celestino, owner of Mezcal La Venia

Dropping into a tiny mountain town on a day with poor weather can be hit or miss. On one hand, some stores are so dead that they close up shop. But on the other, you’ll have the chance at a unique, intimate experience with personal attention that’s hard to come by.

Thankfully for us, our visit to Matalán for a mezcal tour in Oaxaca was the latter. We stumbled upon an artisanal mezcal producer who didn’t just open the doors for us to escape the rain, he also opened his heart and soul for us to better understand what mezcal really is.

Driving to Matatlán for Mezcal

Our morning started off the same way as it does for many tourists around Oaxaca City, checking out the ruins in Mitla. But we had one other thing on our mind that day. Matatlán, a small town less than 30 miles (45km) southeast of Oaxaca City, is well-known for one reason: It’s the mezcal capital of the world. And that’s where we were headed for a DIY tour of mezcal in Oaxaca.

Situated in the heart of an enormous valley, the drive out to Mitla revealed fields of agave ripe for mezcal production. Passing by many distillation facilities caused our thirst for the local spirit to grow. Not going to lie: we love mezcal, maybe a little too much. And that was before this incredible day filled with knowledge and emotion.

We spent the morning in Mitla’s ruins, then grabbed a colectivo (shared taxi) back to Tlacolula, and from there to Matatlán. Going through Tlacolula is the cheapest and easiest way via public transportation whether you’re in Mitla or Oaxaca City (about 60-80 pesos per person to go the whole way, transferring in Tlacolula). You can also take a private taxi directly to Matatlán (more like 300-500 per taxi).

One problem that afternoon: the rain started coming down. Hard. Probably the worst storm during our entire 5-week stay in Oaxaca City.

As we approached Matatlán, it was clear the rain wasn’t going to let up. It was also obvious that many places decided to call it a day and closed up shop. The main street, usually bustling, was more like a ghost town. With expectations low, we threw on rain jackets and went to the closest mezcal place on our list: Mezcal La Venia. It was only a few blocks up the road, but we got soaked by the time we arrived. And a locked gate greeted us. Bummer.

Let’s try knocking… No answer.

Time to stand here for a minute in the pouring rain and ponder our life decisions which led to this moment… Okay, that was fun.

How about we try calling? To our amazement, they picked up.

“Hi! Any chance you guys are around for a small tasting today?! We’ve made the trek our here and are at the entrance.”

“Which entrance?”

“Uhhhh, on the main road?”

“Sure, no problem. We’ll be right there.”

(Rough translation from Spanish.)

And sure enough, with the click of a lock, the metal wheels screeched and the imposing gate rolled away – revealing a trash-filled room.

Uh oh. Time to ponder those life choices once again. But at least we are out of the rain.

Artisanal Mezcal Production

Over the course of the next three hours, we found out that we approached the rear entrance of a lovely mezcal production facility. The front entrance was a beautiful iron gate which led to a garden-filled entrance way, and into the production area. Two large, conical pits flanked a center preparation area, complete with a 4-foot high grinding stone and two copper stills, imbedded deep into concrete. The scene was set.

An assistant immediately offered us a seat. Celestino, the owner, pulled up a chair on the other side and called for two bottles of mezcal: Cuiche and Tobala. That’s when we knew we were in for a treat.

More on our story with Celestino below, but first, time for a little information about mezcal (TLDR at bottom of this section). Many people are familiar with tequila, but mezcal seems to be thought of as some sort of crusaders drink only meant for the adventurers or hipsters. Well, here’s a little secret: if you’ve had tequila, you’ve had mezcal.

Tequila is one (very popular) variety of mezcal, made solely from blue agave. And it’s really only technically tequila if the production takes place in specific Mexican states, mainly Jalisco where the city of Tequila is located. Tequila is to mezcal like bourbon is to whiskey. Mainly semantics.

The differences in mezcal can come from three fundamentals:

- Type of agave used

- Method used to fire and distill

- Time aged

Type of Agave: The most important characteristic of mezcal is the type of agave used to create the spirit. This list is long, there are over 30 different types of agave used for mezcal (some say the list is closer to 150). Agave Azul (blue) is used for tequila, and the most popular outside of that is Espadin. There is also Cuishe (or Cuish, depending on the region), Campo, Coyote, Jabali, Tepeztate, Tobasiche, Tobala, and many more.

One of the greatest challenges with the agave plants is the time it takes for them to grow. Espadin takes only 10-12 years to mature. Yes, a decade is a short period for these plants. Meanwhile, Tepeztate can take 25-35 years! Patience is key. Moreover, some of the most sought-after agave do not grow well in cultivated conditions. So the farmers will incubate the initial growth stages, then plant them where they grow natively. The reliance on shared, public lands makes this profession one full of community and love.

The price of mezcal depends heavily upon the time/difficulty for the agave plant itself to grow. Espadin is usually the cheapest, but not because it is inferior. It’s cheap because it grows quickly and each plant has a large core which provides a lot of mezcal. Others take much longer to grow, can provide a small amount of mash per plant, and can be extremely difficult to germinate (Cuishe, Tobala, & Tepeztate fall into this category).

Method used to fire, distill, and bottle: Once harvested, the leaves, flower stalks, and roots are removed – leaving behind the core known as the piña. This pineapple-looking item, sometimes weighing over 200 pounds, is chopped into large pieces with a machete, then cooked. The piñas used for tequila are often cooked in steam-heated ovens. But other types of mezcal – including most of the flavorful ones – are cooked in large, conical pits about 10 feet in diameter and about 8-10 feet deep. Heated rocks line the base of the pit, then as many as 200 piñas are piled on top, combined with smoldering hardwoods, copal (a hardened tree resin), and agave fibers. Capped off with a layer of earth (dirt) and left smoldering for 3-4 days. This is where the magic happens.

Each piña slowly reveals its true nature, translating into different notes in the final product. Many absorb quite a bit of the smoky flavor, some have very green/grassy tones, some are slightly sweet (fruit, honey, etc.), and others are more earthy. The types of wood used, amount of copal, and other small differences in the roasting process can create a signature trait from the mezcal producer.

The cooked piñas are then ground down using a large stone wheel pulled by a donkey or horse, leaving behind a sweet mash – which is fermented, then distilled in copper or clay stills. The clay ones give a bit more of an earthy flavor, but most of the ones we saw were copper. Most mezcal is distilled at least twice, some more. Producers can add fruits and herbs to the inside of the still to enrich the flavor. And for one variety known as Pechuga, producers hang pieces of raw poultry inside of the still on the third and final round of distillation.

Once the distilled product is complete, it is bottled. Here, water may be added to take the alcohol content down to 35% – 55% alcohol by volume (70-110 proof). A producer can also add other items to the bottle. One is very common: gusano. What’s gusano? It’s a worm from agave plants! Seriously! And it’s good luck to eat the worm once you finish the bottle. Other times mezcal is infused with fruit or herbs, but you’re really messing with the flavor by doing that, so hopefully it wasn’t a great mezcal.

Length of aging process: The three main categories of aging are joven, reposado, and añejo. Joven means young, not aged. They can still have an incredible amount of smoky flavor due to the fire process. Reposado means rested, aged anywhere from 2 to 11 months. And finally, añejo means aged at least 12 months. Joven are incredibly common and many aficionados prefer the purity that the joven method utilizes. Seems odd if you’re used to whiskey (especially scotch), but each agave plant has a distinct flavor and the roasting process does a superb job at bringing that individuality out. Remember – the patience with mezcal lays in the growth stage of the plants themselves. There really isn’t a need to age them to make them better. Plus, aging can be a major challenge in these areas due to the dry climate which is harsh on the aging barrels (the mountains of Oaxaca are semi-arid with long periods of low humidity, and cellars are not common).

TLDR: The type of agave is the most important aspect and provides the most distinction between agave. The fermentation technique usually involves fire-roasting, giving many mezcal a rich, smoky flavor. Finally, the aging process is not mandatory.

Most important tip for buying good mezcal: The labels should specify 100% agave (not mixed with other alcohol), tell you exactly which type of agave is used, where it is from (hopefully somewhere in the state of Oaxaca, if not Matatlán), and specify the length of aging process (joven is the most pure way to start off).

Harsh Realities of Mezcal History

When Celestino at Mezcal La Venia brought out the first two bottles, the taste was unlike any we had tried before. Both were joven (not aged), but had a deep flavor palette. Cuishe was my favorite, and Celestino explained that it is usually meant to have one or two drinks of because of its depth. Kristina loved the Tepeztate and it’s truly unique flavor.

As we got deeper into conversation, Celestino called for a few more bottles. We had to try the Espadin, of course. It was excellent. I think of Espadin as the classic mezcal flavor, and one that you’ll find at many restaurants around Oaxaca as their house drink. It is pure, good to drink a fair amount of, and abundant. We tried a few others of Celestino’s best and we were floored at the distinction between them all – even though they all used the same firing process, distillation techniques, and none were aged.

Here we learned what has happened to mezcal and why tequila took over as the drink that many people associate with Mexico. It’s a sad story. Starting in the 1980’s, the large-scale mezcal producers did not have the patience or care to provide quality mezcal. Rather than wait for the agave to mature appropriately and make entire batches from one type of mezcal, they started to mix all sorts of alcohol in with it. Using other sugars and often corn (essentially moonshine), they bastardized mezcal production. And unfortunately, they sent that out into the world in mass quantities, sold it at a much cheaper price, and tainted mezcal’s reputation. Some of these terrible products are on the store shelves today.

Not surprisingly, Mezcal lost its appeal as a result. But tequila had more stringent standards. You had to use blue agave and had to produce it mainly in the state of Jalisco, Mexico. It retained its true characteristics. Compared to the moonshine-filled mezcal, tequila took over.

But great mezcal is around. Artisan producers who care deeply about their product are still all over in Oaxaca, especially in Matatlán. They wait decades for the plants to grow, prepare the piñas by hand, line the pits carefully, grind the cooked hearts into a perfect mash using a horse-drawn rolling stone, let them ferment well, and distill to perfection. It is an art form. (Is my love for this alcohol coming across as too strong? Uh oh, don’t tell my mom…)

Celestino was born and raised in Matatlán and comes from a line of mezcal farmers. He spoke to us about the drop in demand and the impact on the city there, even opening up about how nearly all of his family left the area to pursue professions outside of mezcal. It was a tearful ordeal for all of us around the table that rainy afternoon. We felt humbled that Celestino sat down with us for so long, shared much about his expertise, and opened up about the troubles of his hometown and family.

But one thing is clear: Mezcal’s comeback is well underway. We were there to share this with you all. To inform you about one of the wonders of Mexico, deep with tradition and made with love. So next time you see mezcal on a menu or in the store, consider Celestino. Consider the complex world that is now within your reach. And become one of the many people opening up their eyes to this incredible spirit.

One final thought: If you take a mezcal tour in Oaxaca with the large company, or rely on top Trip Advisor ratings, you’ll probably end up at something like El Rey Zapoteco or Mezcal Don Agave. Both of these have multiple locations – it’s more like going to the Walmart of mezcal. You’ll learn and taste a lot of good ones, but you’ll feel like a tourist and won’t get the heart-filling experience the smaller artisans provide. So don’t be afraid to seek out something a little farther away from the main tourist track and help this industry thrive again.

So go out and look for a nice bottle of mezcal. And don’t expect it to cost the same as the bottle of Jose Cuervo next to it. Consider each painstaking step that is behind the label and the craftsman sharing his art with the world. Sure, get a cheap bottle if you’re just going to cover up the flavor with tons of lime for margaritas. If you want to know mezcal, the real mezcal, spend the money, sip it slowly, and share it with your loved ones. The best mezcal is sipped alone, but if you really need something to take the edge off, orange slices along with a bit of tajín – or sal de gusano (worm salt) if you can find it – can be served along side.

A big THANK YOU to Celestino and everyone at Mezcal La Venia! You can find out more about this production facility on their facebook page, and whenever you do a mezcal tour in Oaxaca, make sure to set aside a rainy afternoon to share a sip of mezcal with one of the nicest people we have ever met.

“Para todo mal, mezcal, para todo bien, también” (For everything bad, mezcal; for everything good, too.)

Does mezcal sound good to you? Have any other questions about it? Leave us a comment below to let us know!

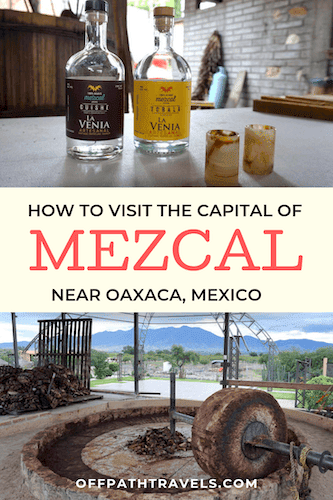

Like This Post? Pin It!

Excellent Article !!

Thanks, David. Glad you enjoyed the article and we hope you’re able to get out and taste the lovely mezcal in Oaxaca. It remains one of our favorite places which we can’t wait to return to!

I imagine we’d need to speak Spanish to enjoy Mezcal La Venia? Would this also apply to getting ourselves around to Mitla and Hierve el Aqua?

Hi Christine! The owner of Mezcal La Venia does know some English and I’d imagine he can give a brief tour of the process, but likely not on a conversational level. There are, however, plenty of other places who offer English-speaking guides. This website looks like it has a great English-speaking tour of family-owned mezcal distilleries, so maybe it’s worth checking out (we have not tried it and are not affiliated with them): http://www.lasbugambiliastours.com/tours/mezcal-distillery/. And there is a Mezcal tour agency that is very active on TripAdvisor and might be able to help out with a private tour as well: https://www.tripadvisor.com/Profile/Mezcal_Tours?tab=forum.

Getting to Mitla and Hierve el Agua can be done quite easily with very little Spanish. If you’re looking to take the colectivos, they have signs in the windshield which say exactly where they are going. To get to Mitla and Hierve el Agua, go to the northeast corner of the large baseball stadium – right in front of the VW dealership – and you will see ones passing with “Mitla” signs in the windshield. Flag them down, ask how much (cuanta cuesta?), and hop in. They drop you off right at a small intersection in Mitla where there are trucks with big signs saying “Hierve el Agua” on top. Or you can just hop in a private taxi and say the destination. Either way, not knowing Spanish shouldn’t be much of a problem.

The only thing you’ll have to confirm and understand is the cost – so understanding numbers in Spanish can go a long way. Learning to count to 100 (or even 1,000) will be VERY helpful, but if worst comes to worst, using fingers to confirm the amount is fine too. Most people in Oaxaca are very understanding of the language barrier and deal with it regularly.

And if you’re interested in learning a bit before heading down, the app Duolingo is a pretty good way to get some basics down.

Yummm. I’m a huge mezcal fan.

It’s amazing stuff! Feels like it could take more than a lifetime to explore it all.